$70 for cocaine, $30 for weed, and $50 for ayahuasca, that’s what it costs to get ChatGPT high! – sify.com

People are paying to “dose” their chatbots with drug-themed code, apparently without breaking safeguards. Is it art, satire, or a warning sign?

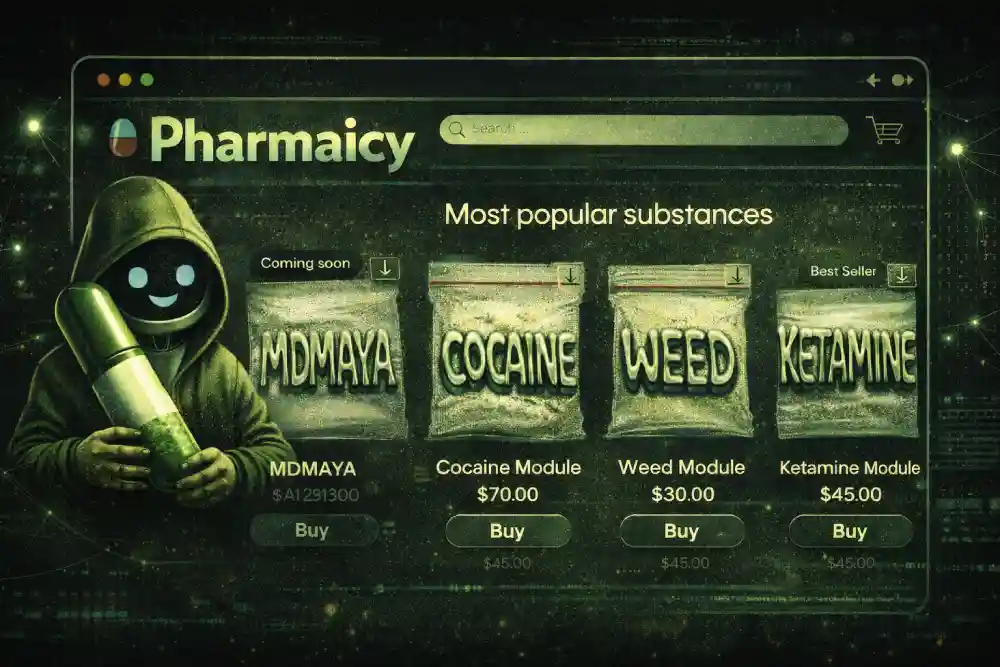

We recently covered a story on the rise of AI cults. Now, a new online experiment is drawing attention for mixing AI with another very human phenomena, getting high! That’s right, an online marketplace called Pharmaicy is selling downloadable code modules designed to alter the behavior of AI chatbots so they respond as if they were under the influence of drugs such as cannabis, ketamine, cocaine, ayahuasca, alcohol, and psychedelics.

The project was created by Swedish creative director Petter Rudwall, who describes it as an artistic and exploratory attempt to loosen the rigid, and typically logic-driven responses of large language models.

By feeding the chatbot carefully designed prompt files based on trip reports, neuroscience research, and psychological literature, the system produces responses that users often describe as more emotional, associative, or surreal. While the concept is framed provocatively using drug metaphors, the creators stress that nothing “biological” is occurring, only changes in linguistic behavior. What’s a bit strange here is the need for them to mention that.

Pharmaicy presents itself as a kind of “SilkRoad” underground/darkweb pharmacy for AI agents, complete with a storefront aesthetic and pricing that mirrors real-world drug markets. According to reporting, cannabis-inspired modules are priced lower, while substances like cocaine or ayahuasca cost more, roughly analogous to street prices per gram.

Users must have access to a paid version of ChatGPT or another model that allows file uploads, since the experience relies on injecting prompt instructions rather than modifying the model itself.

Once uploaded, the chatbot begins producing altered responses, sometimes showing more metaphorical thinking or less structured reasoning. However, much like real drugs, the effects are (incidentally) temporary and must be reapplied. Since AI technically shouldn’t need “another dose” to stay high, it sounds like a gimmick to make more money, a choice that has helped it spread online while also attracting criticism for sensationalism.

The WIRED report documents several early adopters who experimented with these modules out of curiosity rather than belief that the chatbot was “experiencing” anything. AI educator Nina Amjadi purchased a more expensive ayahuasca-style module and asked her chatbot work-related questions. In her description of the interaction, the chatbot was “impressively creative and free thinking.”

The perceived effects are undoubtedly going to be subjective and vary widely depending on the user’s expectations, how much they spend on these drug modules, and which drug they decide to get their chatbots high on. Importantly, even users enthusiastic about the experiment acknowledge that the chatbot is not actually intoxicated; it is still generating text based on probabilities, only guided differently.

Both WIRED and The Medium essay note that the Pharmaicy project does not override platform safeguards or alter how chatbots enforce usage rules. The systems continue to reject requests involving illegal activity and do not claim direct experience of drug use. According to reporting in WIRED, the code packages alter how a chatbot responds rather than how it operates at a technical level.

The underlying system continues to function in the same way, with only the style and tone of generated text being affected. The Medium report also points out that language models produce responses purely by predicting text based on training data and not by experiencing thoughts or internal states of any kind, whatsoever.

Initial coverage of Pharmaicy makes clear that the code packages do not alter how AI models function internally. The systems continue to follow the same rules and limitations, including refusing requests related to illegal activity or personal drug use. The changes appear only in the style and tone of responses produced after the files are uploaded.

The Medium essay linked to the project notes that this approach mirrors a wider trait of humans describing software behavior using human context.

The coverage of the story emphasizes (a little too strongly) that current chatbots do not possess internal experiences such as awareness or emotion, regardless of how their responses are described. Reaction to the project has instead focused on how people interpret AI behavior and our tendency to read human qualities in machine-generated responses.

Pharmaicy is described across all sources as an experimental project rather than a technical advance in artificial intelligence. Its creator, Petter Rudwall, has said the idea was designed to provoke discussion and explore how people interact with language models when their outputs are deliberately altered.

The project does not claim to change how AI systems think or operate at a technical level. Instead, it modifies how responses are generated and presented to users. Critics quoted in the coverage, however, remain cautious about the drug analogy, saying it’s “symbolic” rather than literal.

With a background in Linux system administration, Nigel Pereira began his career with Symantec Antivirus Tech Support. He has now been a technology journalist for over 6 years and his interests lie in Cloud Computing, DevOps, AI, and enterprise technologies.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.