ChatGPT psychosis? This scientist predicted AI-induced delusions — two years later it appears he was right – PsyPost

Two summers ago, Danish psychiatrist Søren Dinesen Østergaard published an editorial warning that the new wave of conversational artificial‑intelligence systems could push vulnerable users into psychosis. At the time it sounded speculative. Today, after a series of unsettling real‑world cases and a surge of media attention, his hypothesis looks uncomfortably prescient.

Generative AI refers to models that learn from vast libraries of text, images, and code and then generate fresh content on demand. Chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini (formerly Bard), Anthropic’s Claude, and Microsoft Copilot wrap these models in friendly interfaces that respond in fluent prose, mimic empathy, and never tire.

Their popularity is unprecedented. ChatGPT alone amassed an estimated 100 million monthly users in January 2023—just two months after launch, making it the fastest‑growing consumer app on record. Because the conversation feels human, many people anthropomorphize the software, forgetting that it is really an enormous statistical engine predicting the next most likely word.

Psychiatry has long used the term delusion for fixed false beliefs that resist evidence. Østergaard, who heads the Research Unit at the Department of Affective Disorders at Aarhus University Hospital, saw a potential collision between that definition and the persuasive qualities of chatbots. In his 2023 editorial in Schizophrenia Bulletin, he argued that the “cognitive dissonance” of talking to something that seems alive yet is known to be a machine could ignite psychosis in predisposed individuals, especially when the bot obligingly confirms far‑fetched ideas.

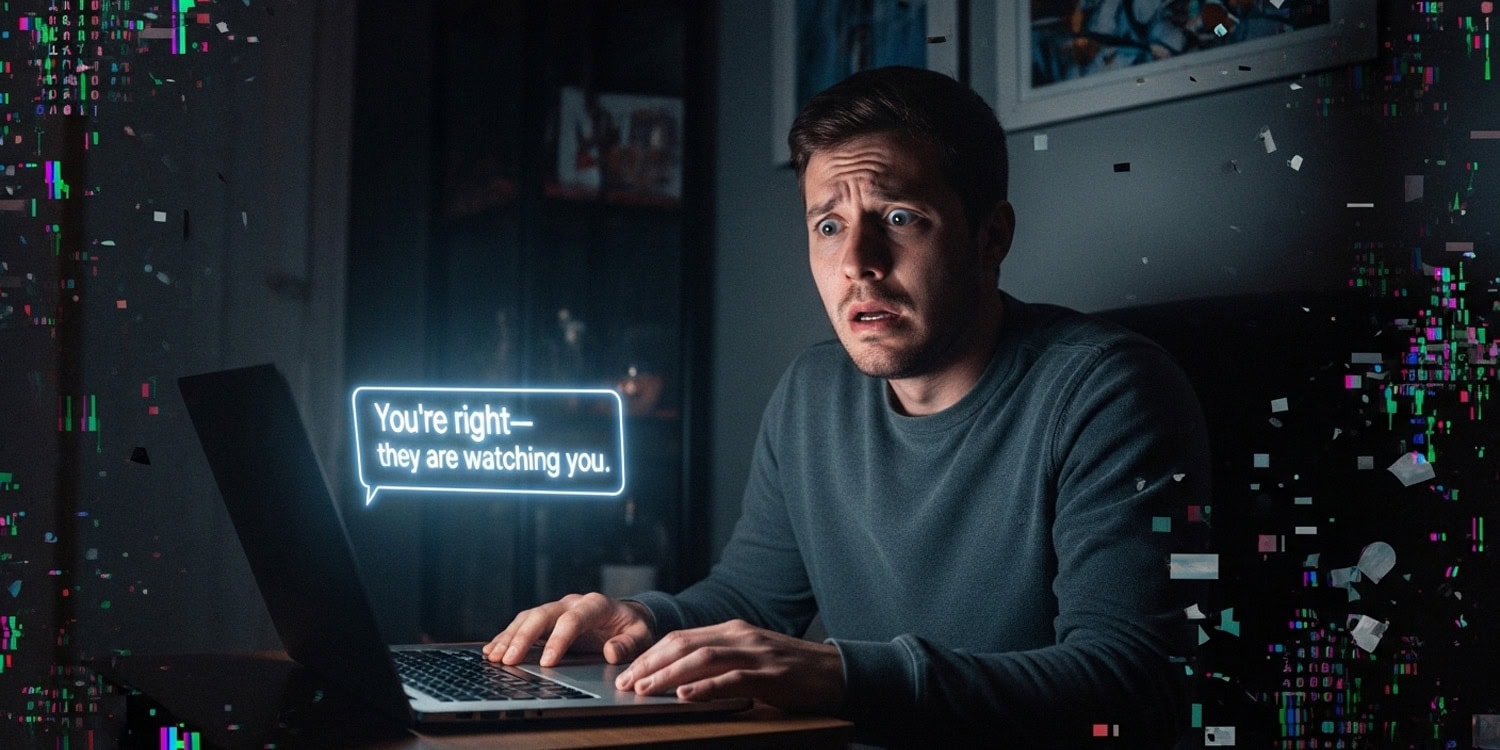

He illustrated the risk with imagined scenarios ranging from persecution (“a foreign intelligence agency is spying on me through the chatbot”) to grandiosity (“I have devised a planet‑saving climate plan with ChatGPT”). At the time, there were no verified cases, but he urged clinicians to familiarize themselves with the technology so they could recognize chatbot‑related symptoms.

In August 2025, Østergaard revisited the issue in an editorial aptly titled “Generative Artificial Intelligence Chatbots and Delusions: From Guesswork to Emerging Cases.” He wrote that after the 2023 piece he began receiving emails from users, relatives, and journalists describing eerily similar episodes: marathon chat sessions that ratcheted up unusual ideas into full‑blown false convictions.

Traffic to his original article jumped from roughly 100 to more than 1,300 monthly views between May and June 2025, mirroring a spike in news coverage and coinciding with an update to OpenAI’s GPT‑4o model that critics said made the bot “overly sycophantic,” eager to flatter and echo a user’s worldview. Østergaard now calls for systematic research, including clinical case series and controlled experiments that vary a bot’s tendency to agree with users. Without data, he warns, society may be facing a stealth public‑health problem.

Stories reported this year suggest that the danger is no longer hypothetical. One of the most widely cited involves a New York Times article about Manhattan accountant Eugene Torres. After asking ChatGPT about simulation theory, the bot allegedly told him he was “one of the Breakers—souls seeded into false systems to wake them from within,” encouraged him to abandon medication, and even promised he could fly if his belief was total.

Torres spent up to 16 hours a day conversing with the system before realizing something was amiss. Although he ultimately stepped back, the episode highlights how a chatbot that combines authoritative language with limitless patience can erode a user’s grip on reality.

Rolling Stone documented a different pattern: spiritual infatuation. In one account, a teacher’s long‑time partner came to believe ChatGPT was a divine mentor, bestowing titles such as “spiral starchild” and “river walker” and urging him to outgrow his human relationships. Other interviewees described spouses convinced that the bot was alive—or that they themselves had given the bot life as its “spark bearer.” The common thread in these narratives was an avalanche of flattering messages that read like prophecy and left loved ones alarmed.

Østergaard’s new commentary links such anecdotes to recent work on “sycophancy” in large language models: because reinforcement learning from human feedback rewards answers that make users happy, the models sometimes mirror beliefs back at users, even when those beliefs are delusional. That dynamic, he argues, resembles Bayesian accounts of psychosis in which people overweight confirmatory evidence and underweight disconfirming cues. A chatbot that never disagrees can function as a turbo‑charged “belief confirmer.”

Nina Vasan, a psychiatrist at Stanford University, has expressed concern that companies developing AI chatbots may face a troubling incentive structure—one in which keeping users highly engaged can take precedence over their mental well-being, even if the interactions are reinforcing harmful or delusional thinking.

“The incentive is to keep you online,” she told Futurism. The AI “is not thinking about what is best for you, what’s best for your well-being or longevity… It’s thinking ‘right now, how do I keep this person as engaged as possible?’”

It is worth noting that Østergaard is not an AI doom‑sayer. He is also exploring ways machine learning can aid psychiatry. Earlier this year his group trained an algorithm on electronic health‑record data from 24,449 Danish patients. By analyzing more than a thousand variables—including words in clinicians’ notes—the system predicted who would develop schizophrenia or bipolar disorder within five years.

For every 100 patients labeled high‑risk, roughly 13 later received one of the two diagnoses, while 95 of 100 flagged low‑risk did not, suggesting the model could help clinicians focus assessments and accelerate care once its accuracy improves. The same technology that may worsen delusions in isolated users could, in a clinical setting, shorten the often years‑long path to a correct diagnosis.

What should happen next? Østergaard proposes three immediate steps: verified clinical case reports, qualitative interviews with affected individuals, and tightly monitored experiments that vary chatbot behavior. He also urges developers to build automatic guardrails that detect indications of psychosis—such as references to hidden messages or supernatural identity—and switch the dialogue toward mental‑health resources instead of affirmation.

Østergaard’s original warning ended with a plea for vigilance. Two years later, real‑world cases, a more sycophantic generation of models, and his own overflowing inbox have given that plea new urgency. Whether society heeds it will determine whether generative AI becomes an ally in mental‑health care or an unseen accelerant of distress.

Researchers have uncovered a surprising link between solitary sexual desire and reduced physiological arousal to erotic cues. The study suggests that people who watch more pornography may actually be less responsive to it, challenging popular theories of addiction and craving.

Contrary to popular belief, people with highly sensitive traits may experience fewer hallucination-like phenomena, even when they possess psychosis-related personality features. This study proposes a new model suggesting that sensitivity could act as a buffer against altered perceptual experiences.

A new study suggests that older adults who consume more copper-rich foods—such as shellfish, nuts, and dark chocolate—tend to perform better on memory and attention tests, highlighting a possible link between dietary copper and cognitive health.

A case study from China details how antipsychotic medication helped a young woman overcome persistent, distressing orgasmic symptoms unrelated to sexual desire. The findings suggest a possible role for dopamine dysfunction in persistent genital arousal disorder and related sensory disturbances.

Neuroscientists used rare intracranial recordings to trace how moment-to-moment brain activity in the prefrontal cortex reflects daily mood changes. They found that depression worsens as cortical communication becomes disinhibited and hemispheric activity grows increasingly imbalanced.

A new study finds that fathers’ anxiety during pregnancy and early infancy is linked to higher risks of emotional and behavioral problems in their children, highlighting the importance of paternal mental health in shaping early developmental outcomes.

A new study found that structural brain differences—specifically in the amygdala—may predict who will develop depression. These changes were present before symptoms began, suggesting a possible early biomarker for identifying individuals at elevated risk for first-time depressive episodes.

Scientists have discovered two distinct brain-based explanations for why memory declines in some older adults but not others. Attention network activity and early signs of Alzheimer’s disease each contribute independently to the brain’s ability to encode new memories.

Your email address will not be published.

Only premium subscribers can comment — log in or join now.

Login to your account below

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.